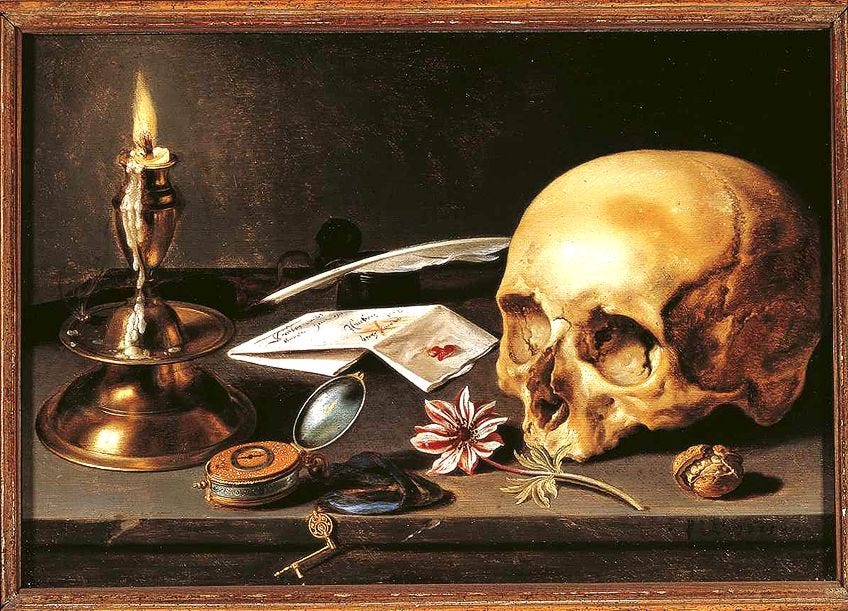

During the month of November, Catholics around the world pray specifically for the dead, those preparing to die, and the souls stuck in purgatory. This is a time when the phrase memento mori meaning “remember your death,” is quoted quite often. It’s a popular phrase not meant to invoke a macabre spirituality, but a humble expression of faith in the Resurrection of Christ. There is a spiritual power in remembering that we are finite creatures. In remembering that our lives are short and how we live them is important.

There was time after I was first diagnosed that the doctors were not able to identify what caused my chronic illness and could only run so many tests since my blood counts were so low. They could only make guesses and were pointing in the direction of cancer being the root cause of what was happening to me. Praise the Lord that it was not, but for weeks, every doctor I met with alluded to “lymphoproliferative diseases.” Big words they used to avoid scaring me with the actual word “cancer.” At one point I had told the doctor I saw in one of the many ER visits that I wasn’t scared of the word and if that’s what he thought I had, then please just stop skirting around the bush and come out and say it!

During the time that doctors thought it could be a type of cancer, I thought I would be more scared. I thought I would stay up all night crying or scared to talk about what life would be like should I receive that kind of diagnosis. Instead, there was healthy amount of fear in the potential length and effect of treatment, but I found that talking about it openly eased my mind rather than just keeping it to myself. My family and I used humor, like always, to diffuse the fear that could have easily taken over my peace of mind. While it may sound morbid, we made contingency plans if I needed to shave my head or what kind of casket I would want since the type of cancer they thought I had was terminal. Has anyone ever seen those wrapped caskets where you can put any design you want on them? That was exactly what I wanted: I pictured sunflowers, a bible verse or two, and a picture of me because there was no way I was going to allow an open casket at the viewing.

We were very aware that not everyone was comfortable with those kind of jokes, but honestly, it made the thought of dying easier to stomach. If this was going to be worse case scenario, we might as well find a way to laugh. In fact, when my mom had cancer about a decade ago, we laughed at very similar jokes. It is our family’s way of coping with the most human confrontation we all face: death.

I think what made the idea of potentially dying easier to bear was that I would be so much closer to the Lord than while I was alive. While living on earth, we are physically separated from God in Heaven and death is the door that bridges that gap. As creatures of flesh, we are still affected by original sin and cannot have full communion with God in body and soul until the Second Coming of Christ. Death is one step closer to that full union. The time spent waiting for that final reunification is described by my favorite two theological words: eschatological tension.1

That gorgeous $5 word combo refers to the paradoxical reality that while God’s kingdom has already been inaugurated through the Life, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, its full realization is still to come at the end of time. This tension exists between the "already" — the spiritual realities brought about by Christ’s first coming — and the "not yet" — the future fulfillment of God’s promises in the Second Coming.

Catholics believe that salvation and the possibility of eternal life are already accessible through Christ, yet the complete victory over sin, death, and suffering is still awaited. This tension influences the way Catholics live out their faith, balancing the present experience of grace with the hopeful anticipation of Christ’s return, when all will be made new and God’s justice fully realized.

1 Corinthians 15 is one of the prevailing texts here:

“This I declare, brothers: flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does corruption inherit incorruption. Behold, I tell you a mystery. We shall not all fall asleep, but we will all be changed, in an instant, in the blink of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, the dead will be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed. For that which is corruptible must clothe itself with incorruptibility, and that which is mortal must clothe itself with immortality. And when this which is corruptible clothes itself with incorruptibility and this which is mortal clothes itself with immortality, then the word that is written shall come about:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.

Where, O death, is your victory?

Where, O death, is your sting?”The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore, my beloved brothers, be firm, steadfast, always fully devoted to the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain.” (1 Cor 15: 50-58)

This eschatological tension directly relates to the practice of memento mori, since it is a call to live in constant awareness of death’s inevitability and the transient nature of earthly life, urging individuals to remain vigilant and prepared for the final judgment. The tension between the "already" and the "not yet" of the Kingdom of God invites Catholics to live with a sense of both hope and urgency. While they experience God's grace in the present, they are reminded to orient their lives toward the future reality of eternal life, where death will be conquered and perfect communion with God will be realized. Memento mori becomes a way of embracing this tension, fostering a deeper awareness of mortality and encouraging a life of holiness and readiness for Christ’s return.

During the Eucharistic Prayer at Mass, after the consecration, the people are invited to acclaim this Mysterium Fidei (Mystery of Faith). This simple acclamation proclaims the belief in the Resurrection of the Lord. We acknowledge His death and we also proclaim our faith that He will come again to judge the living and the dead.

We proclaim your Death, O Lord,

and profess your Resurrection

until you come again.

When I received the news that I didn’t have terminal cancer, but rather a lifelong illness, there was relief since the suffering that was avoided was monumental. However, to be completely honest, there was a small part of me that did wish it was a terminal diagnosis. It sounds crazy, morbid, and perhaps a bit insensitive, but in my mind at the time, I thought it would bring me so much closer to reaching the goal of Heaven and the second coming of Christ. I thought that if I could suffer and die a holy death like Bl. Chiara Badano, perhaps I, too, had the chance of reaching heavenly beatitude. Truth be told, I viewed that kind of suffering like a form of martyrdom.

At 17, Chiara was diagnosed with terminal cancer and despite doctor’s best efforts, there was no medicine or surgery that could have cured her. She underwent immense amounts of pain and suffering, eventually losing her ability to walk and speak. However, she offered every shred of suffering for Jesus. Her infectious smile and positive personality spread hope and peace to her immediate family and friends who constantly surrounded her bedside. Though initially scared at the thought of death, she came to eagerly await her final moments in the hope of meeting Jesus. She gracefully lived in that tension between the “already” and the “not yet.”

“For you, Jesus: if you want this, so do I!”2

Her short life was filled with beautiful moments of surrendering to her imminent death. She lived under the auspices of memento mori, knowing that despite the inevitability of her death, she would live her fleeting moments on earth filled with the joy of Christ. I like to think that I have expressed that level of faith throughout my own illness journey, but it’s hard not to compare and awknowledge how far I am from this young girl’s expression of true devotion and faith. Her mature sense of accepting the diagnosis found permissible as God’s will for her life.

However, it is not God’s will that I experience that kind of faithful intimacy with Him through a terminal illness. Instead, I have smaller crosses with smaller physical effects that I can offer up in an effort to unite my cross with His. I can keep the reality of death before my eyes as I strive to grow in virtue and grace; while also accepting the current circumstances God has placed me in.

It was honestly harder than I thought to accept that I didn’t have a terminal illness because I thought that being terminally ill automatically brought you closer to God. A very immature and prideful view of the spiritual fruits hard earned by those who suffer for them. In a way, I was looking at having cancer as short cut to Heaven which it very much is NOT.

God in His own way is bringing me closer in relationship to Him through a path that I would not have chosen for myself, but He did. With this illness, there are certainly complications and risks, but I am not scared because if I continue to strive to live my life in accordance with His will, I have nothing to fear. My goal is Heaven and however long it take me to get there, it will be worth the struggles I face now.

This life is precious with every moment existing as both a gift and mystery. One day, at the time of our death, we will look upon the One who loves us. His kingdom and our relationship with Him will endure into eternity, when we have left all we know of this world behind us. The trick is learning how to wait.

Talk to you soon,

Ryleigh

https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/cti_documents/rc_cti_1990_problemi-attuali-escatologia_en.html

https://www.chiarabadano.org/en/life/#ultimi

Suffering can be redemptive. Thank you for sharing and you have my prayers.

I continue to be amazed by your candor, and the beauty with which you profess your deep faith in the church of Jesus Christ. is the recipient of three chronic illnesses over my 61 year lifespan, I can empathize, and am also humbled, by your witness.

“It is our family’s way of coping with the most human confrontation we all face: death. “

This is so healthy. I lost an aunt and an uncle to cancer, in their seven children were similarly coping. It blew me away at the time. Now I understand better! Thanks!